Habits of BC Fish

Salmon and Steelhead

While salmon and steelhead will consume food in fresh water under some circumstances, they are mostly concerned with surviving the migration and spawning.

To consistently catch salmon and steelhead you must become familiar with the timing of the run and understand where the fish are most likely to hold. Call a fishing guide service near the river you intend to fish, they’ll tell you when to expect the best fishing.

Plan your trip around that information. If your schedule is flexible, wait until the run is actually underway and then go. Even the most knowledgeable, local predictions can be frustrated by unusual weather patterns. Drought will often delay a run, while heavy precipitation may bring the fish in earlier than usual. Ocean currents, like El Nino, and commercial fishing can also have an effect.

When you know the fish are in the river, look for water that would be an attractive holdover spot or migration route for moving fish. Local knowledge is priceless in this regard, as the same pools are usually the best producers season after season. You may also want to just drive along a section of the river, watch the access points, and study the types of water other anglers are concentrating on.

Once you know what type of water your quarry prefers, you can fish any stretch of the river and be successful. In moving water, fish usually hold in certain locations and wait for the food to drift to them. Look first for breaks in the current. Some of the best locations are fallen trees, in-stream rocks, gravel banks, current seams behind islands, deep depressions, weedy bends, above riffles, back eddies, steep banks, riffles, and submerged boulders or obstructions.

The Story of the Salmon

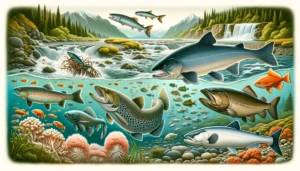

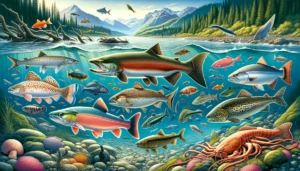

Characterized by grace and beauty, a silvery sheen and spotted back and fins, our beautiful Pacific Salmon.

An anadromous animal, the Pacific Salmon breeds and spends varying portions of its life in fresh water, then travels to the ocean to feed until maturity. This is in contrast to pelagic species which are born and live solely in the sea. Each of the five species of Salmon differs in its life history, with Pinks, for example, living only two years and reaching a weights of five plus pounds, while the giant chinook can reach over 90 pounds and lives for up to seven years.

Salmon are born in gravel beds in streams anywhere from a hundred yards to 1000 miles from the sea. Laid in the fall, the eggs incubate for several months and then hatch. In the river, or a nearby lake, depending on the species, they feed and grow for periods ranging up to a year or more. Then in the spring, during the season of freshets, they head downstream to the sea. In the sea they spend varying amounts of time ranging up to five years, eating greedily and growing rapidly in the bountiful ocean feeding grounds. In early summer of their maturing year they begin to head back to their home streams, navigating by their simply incredible sense of smell.

When reaching freshwater they struggle, often for weeks or months, against rapids, falls, obstructions in the form of fallen logs and rocks until, bruised and travel-worn they reach the placid waters of the spawning river where they were born. The female digs a redd, in the gravel, hollowing out a cavity up to 18 inches deep. She prefers a place in a riffle, where the fast-running water will provide an ample supply of oxygen for the eggs. When the redd is ready, which may be weeks after the spawner has reached the gravel beds, the female lays her eggs. Up to 15,000 eggs are deposited in the gravel, and soon after, the male fertilizes them by covering them with a milky substance known as milt.

With spawning over, the salmon’s life is complete, and within a short time it dies, and the body in turns nourishes the river.

In the ocean, the Sockeye, Pinks and Chums feed primarily on plankton and crustaceans such as tiny shrimp, while chinook and coho eat smaller fish, making them vulnerable to commercial and sports fishermen using bait such as herring. Sockeye and Chinook are the most hardy of the family, travelling as far as 1,000 miles upstream to spawn. Chums, Coho and Pinks usually spawn closer to the sea.

Pacific Salmon Spawn – The Return of the Salmon

Trout

Trout are coldwater fish, so you will find them in rivers and lakes that have cold water year-round. In rivers, trout face upstream so the water flows into their faces, bringing drifting food to them.

Like bass and panfish, they spend all their time eating, resting, and hiding from predators. When they are resting, river trout hide under currents, near the bottom of deep pools, under shoreline structures such as logs, brushy banks, undercut banks and boulders.

When they are feeding, stream trout move to where the food comes to them, eddies (anywhere there is a break in the flow, creating a fast current beside slow-moving water), along weedbeds, behind boulders, at the tailouts of pools, and in early morning or late evening, in the stream shallows.

You can locate feeding trout (also bass and panfish) by the dimples they make when they take insects off the water’s surface. You can locate nymphing trout (fish eating nymphs beneath the surface) by looking down into the water (using polarized sun glasses) and spotting their sides flashing as they feed.

Lake trout cruise in search of their food. Look for them along weedbeds, a prime location for the insect life that trout feed on. Also look for their rise rings (dimples they make when feeding on the surface) on the lake. Trout often cruise the surface to “gulp” aquatic insects that are hatching.

Certain areas of a lake are more likely to hold fish than other areas. Some more rewarding places are where freshwater enters the lake, fallen trees, sand or gravel bars, rock piles, steep banks, overhanging brush or trees, weedy coves, submerged weedbeds and underwater points.

Trout will often cruise from one location to another.

Bass

Bass capture their food by ambush, and because they prey on panfish, they often lie in or near the same places that panfish are found. These larger predators dash out from their hiding places to snatch moving minnows, panfish, frogs and crayfish.

In lakes and ponds, expect to find them prowling or lurking around lilypads, weedbeds, boat docks, logs, overhanging trees or any man-made structure that they can hide underneath. Look for bass around headlands, jetties, reefs or along the shoreline.

Remember that larger bass usually live in or near the deeper holes. The larger the fish, the more depth it needs for protection and food.

https://www.pac.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/fm-gp/species-especes/salmon-saumon/habitat-eng.html