Vancouver, Coast & Mountains

The Vancouver, Coast & Mountains region of British Columbia includes the metropolitan city of Vancouver, the all-season resort village of Whistler, the Sunshine Coast, and the Fraser Valley on the BC Lower Mainland. Highway 99, the Sea to Sky Highway, winds alongside picturesque Howe Sound through Squamish to Whistler Blackcomb, and farther on to Pemberton and Lillooet. Highway 7 and the Trans-Canada Highway 1 run north and south of the Fraser River through Abbotsford and Chilliwack to Hope and on to the Okanagan Valley.

Greater Vancouver

Greater Vancouver is viewed as a staging area for adventures in the wilder territories of the province. This region contains one of the most urbanized areas in Canada, yet teems with parks, beaches, and cycling and walking destinations. On every corner, it seems, there is a pocket of green space.

- Burnaby

- Coquitlam

- Delta

- Fort Langley

- Fraser Estuary

- Granville Island

- Greater Vancouver

- Ladner

- Langley

- Maple Ridge

- New Westminster

- North Shore

- Pitt Meadows

- Port Coquitlam

- Port Moody

- Richmond

- Steveston

- Surrey

- Trans Canada Highway 1

- Tsawwassen

- Vancouver

- Vancouver Airport (YVR)

- Vancouver Downtown

- White Rock

The North Shore

On a clear day, few skylines can compete with the one composed of the North Shores’ six mountain peaks. After a rainstorm, the brilliant black-green hue of the North Shore shines with freshness. When snow coats the slopes, they sparkle so perfectly your heart sings at the sight.

The Fraser Valley

The wide, fertile Fraser Valley is spread between the Coast and Cascade Mountains, parallel with the Canada-US border. The valley runs more than a hundred miles inland from the Pacific to the small town of Hope at its eastern end. You can drive from one end of the Fraser Valley to the other in about two hours.

- Abbotsford

- Abbotsford Airport (YXX)

- Agassiz

- Aldergrove

- Boston Bar

- Bridal Falls

- Chilliwack

- Cultus Lake

- Fraser Valley

Whistler/Sea to Sky

Intensely scenic, the Sea to Sky Highway crosses paths with two historic routes, the Pemberton Trail and the Gold Rush Heritage Trail, which linked the coast with the interior in the past. Along these ancient pathways, generations of Coast Salish people traded with their relations in the Fraser Canyon.

The Sunshine Coast

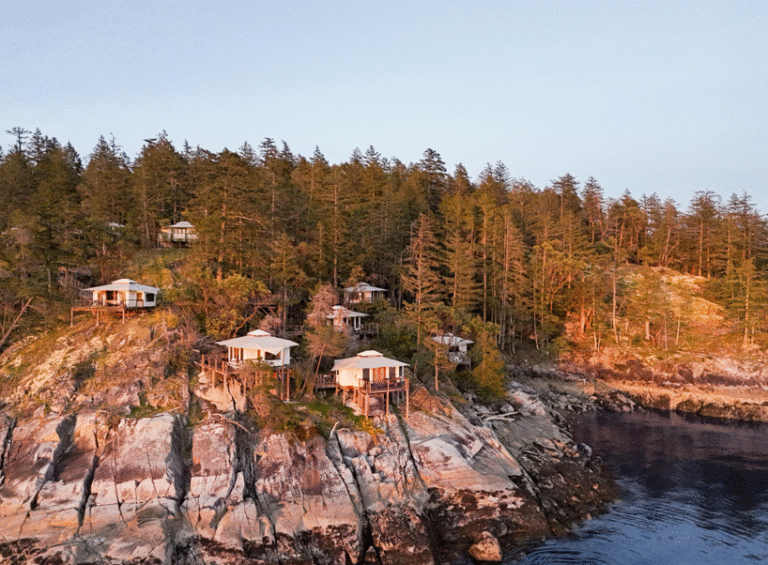

A secluded world of beaches, bays, islands and fjords overlooked by B.C.’s majestic Coast Mountains, the Sunshine Coast stretches 180km along the Strait of Georgia, from Howe Sound to Desolation Sound. The Sunshine Coast lives up to its name, with bright days outnumbering gloomy ones by a wide margin.

- Bute Inlet

- Desolation Sound

- Earls Cove

- Egmont

- Gambier Island

- Garden Bay

- Gibsons

- Halfmoon Bay

- Highway 101

- Howe Sound

- Irvines Landing

- Jervis Inlet

- Keats Island

- Lang Bay

- Langdale

- Lund

- Madeira Park

- Pender Harbour

- Powell River

- Roberts Creek

- Salish Sea

- Saltery Bay

- Savary Island

- Sechelt

- Secret Cove

- Sliammon

- Sunshine Coast

- Texada Island

- Toba Inlet

- Wildwood

Greater Vancouver

About the only thing Vancouverites seem to enjoy doing more than being outside is complaining about the weather. If you can’t take a joke, why live in the rain forest? As for the price residents pay to live here, it helps to think of Vancouver as a destination resort. Fortunately, one of the trade-offs for paying your dues in Lotus Land is the wonderful array of public gardens, parks, and beaches where residents and visitors alike frolic. You can always count on there being enough room for you to play somewhere around town.

Here are a few pointers on where to find the action, and where to avoid the crowds. To begin, it’s important to understand the layout of the city. In 1792, when Captain Vancouver first sailed into English Bay and Burrard Inlet, he found a sheltered, deep-water harbour. (One discovery he overlooked was the mouth of the Fraser River. That remained hidden from Europeans until Simon Fraser and his crew of transcontinental adventurers completed their voyage to the Pacific Ocean by canoe in 1808.) Not long ago, it used to be easy to distinguish Vancouver from its neighbours. Bridges spanned Burrard Inlet and the Fraser River to connect with communities to the north and south, while buffer zones of undeveloped land defined where the Big Smoke left off and all else to the east began.

By the 1970s, such distinctions had blurred to the point where one hardly noticed a transition from one city to the next, particularly between Vancouver, Burnaby, New Westminster, and Port Moody. Today, Vancouver is just one swatch in a quilt of 23 cities, municipalities, villages, districts, and even a township. Although each still maintains its own history, flavour, and relative autonomy, together they form the Greater Vancouver Regional District (GVRD). There is a vast amount of green spaces and outdoor activities to take advantage of in this little corner of the province. From Bowen Island to Matsqui, the GVRD covers a swath of land 30 miles (50 km) long from the Strait of Georgia east into the Fraser Valley, and about the same distance wide from the North Shore Mountains to the Canada-US border.

Among its many duties, the GVRD stewards 22 parks that range in size from diminutive Grant Narrows to massive Lynn Headwaters. Include the GVRD’s Seymour Demonstration Forest in the tally, and the total protected area is more than 41,480 acres (16800 hectares). At the same time, BC Parks, the provincial parks department, also maintains a considerable presence around Greater Vancouver. For example, Cypress Provincial Park in West Vancouver is the busiest in the province, hosting more than a million visitors a year. The range of activities that visitors can pursue inside these parks encompasses all possible modes of exploration – biking, fishing, hiking, skiing, paddling, swimming – even driving!

Many people – residents and visitors alike – view Greater Vancouver as a staging area for adventures in the wilder territories of the province. This region contains one of the most urbanized areas in Canada, with all the attendant benefits and drawbacks that implies. Even so, it’s surprisingly easy to get around the metropolitan core, which teems with parks, beaches, and cycling and walking destinations. On every corner, it seems, there is a pocket of green space. In the midst of concrete and glass will be an oasis of trees and grass. From the famous Stanley Park to the infamous Wreck Beach, Vancouver is awash with outdoor possibilities. Add to that its world-class restaurants and attractions, and you have enough activities to keep you in this corner of the universe forever. Vancouver is one of the most desirable cities on the planet to explore. It’s time you checked it out for yourself.

The Fraser Estuary

The term Lower Mainland came into currency among Vancouver Island settlers in the 19th century. Early immigration into the Crown Colony of British Columbia from Asia, Australia, Hawaii, Newfoundland, Europe, the United States, and Mexico spilled over from Vancouver Island into the lush farmland of the Fraser Estuary and Fraser Valley. Mainlanders became a term used by island residents to emphasize the separation, and perhaps the feeling of superiority, between the two. The Strait of Georgia that divides Vancouver Island from the Lower Mainland represents a psychological schism as much as it does a physical split.

Just as Vancouver is blessed by its proximity to the North Shore mountains, so too is it graced by the Fraser River’s union with the Pacific Ocean. Riverside trails, intertidal wetlands, a delta of low-slung islands and a catalogue of wildlife accompany the mighty waterway. As you make your way through the Fraser River Estuary you are always aware of the silent weight of the Fraser, to which the landscape owes its existence. Much of the estuary has come into being only in recent times – geologically speaking – a fact attested to in the oral history of the Musqueam people, whose ancestors witnessed the islands at the mouth of the Fraser take shape. As the estuary silts in at a regular annual rate, it’s as easy to gauge the increase in its size as it is to measure the growth of a tree. In an age of diminishing expectations, it’s reassuring to know that in the Fraser Estuary, at least, there’s an expanding quantity of soft, rich soil and broad, muddy water to explore!

The Fraser Valley

The wide, fertile Fraser Valley, yet another aspect of the Lower Mainland’s landscape, is spread between the Coast and Cascade Mountains, parallel with the Canada-US border. The valley runs more than a hundred miles inland from the Pacific to the small town of Hope at its eastern end. You can drive from one end of the Fraser Valley to the other in about two hours. You can just as easily spend a lifetime exploring the 150 km between Vancouver and Hope. With half the population of British Columbia living in or within easy driving distance of the Fraser Valley, the question of where to head in advance of the crowds is a challenging one.

From an explorer’s perspective, Forest Service recreation sites and provincial parks pick up where Greater Vancouver Regional District (GVRD) parks leave off. Except for the cities of Maple Ridge and Mission on the north, and Abbotsford and Chilliwack south of the Fraser River, this is a prairie realm where cowboy boots and Stetsons aren’t out of place. Almost all of the fertile land is rural and supports a blend of farming, forestry, and outdoor recreation. Fraser Valley residents are just as keen on using these parks and trails as their neighbours in the GVRD. One of the benefits of living out in the valley is knowing the best spots and having a head start in reaching them, especially on summer weekends. If you can be on one of the many backroads by 3pm on Friday, you’re well on your way to securing a campsite. Rest assured that at other times of the week you will have your pick of sites.

Since the 1980s, the population explosion in the Lower Mainland has exerted considerable pressure on the Fraser Valley. Fortunately, much of the lush farmland is protected under the provincial Agricultural Land Reserve Policy instituted in the 1970s. Demographic analysis of growth patterns from now to the mid-21st century suggests a continual erosion of this rural landscape. With this in mind, in the mid-1990s the provincial government accepted a committee’s recommendation that almost 14 percent of the land base be set aside for parks. This was welcome news for outdoor enthusiasts, many of whom actively supported the preservation of critical wilderness corridors found in places such as the Skagit Valley in the south Fraser Valley and the Pitt Lake region in the north. The signing of the provincial Protected Areas Strategy Accord in October 1996 signaled a victory for conservationists who had worked for the protection of such pristine areas since the mid-1970s. Now it’s time to get out there and enjoy the 14 percent solution.

The North Shore

There’s an old saying that if you can see the North Shore from Vancouver, it’s about to rain, and if you can’t, it is raining. Rain is part of the price residents on the steep-sided slopes of West and North Vancouver pay for living on the wild side of Burrard Inlet. Clouds bump up against the forested mountainside, become ensnared in dense stands of Douglas fir and hemlock, and linger long after skies have opened over Vancouver. This is a moody locale. On a clear day, few skylines can compete with the one composed of the Shores’ six peaks – Black, Strachan, Hollyburn, Grouse, Fromme, and Seymour Mountains. After a rainstorm, the brilliant black-green hue of the North Shore shines with freshness. When snow coats the slopes, they sparkle so perfectly your heart sings at the sight.

Before the construction of the original Second Narrows Bridge in 1925, the North Shore was a world apart. Ferries once linked Ambleside in West Vancouver with Vancouver. From Ambleside, hikers in summer and skiers in winter would make their way up the side of Hollyburn Mountain, at first on foot or by wagon, later by car and bus. Cabins were constructed, trails brushed out. Grouse and Seymour Mountains developed in much the same way, though Grouse has always been the leader in commercial development. Mountain tops were the perfect places to get away from dirty old Vancouver, especially in cool weather. Before the Second World War, sawdust was the fuel of choice in many Vancouver homes, darkening the air with its soot.

Much has changed since Navvy Jack Thomas became the first European to permanently settle on the North Shore in the 1880s. Today, thousands of visitors walk and hike where Chief Joe Capilano first guided poet and outdoorswoman extraordinaire Pauline Johnson, the most popular Canadian entertainer of her time, along the ancient North Shore trails. Johnson, the daughter of a Mohawk chief and an Englishwoman, wrote Legends of Vancouver, published in 1911, two years before her death. The tales she transcribed still bear repeating, such as the story of the two sisters who, long before Captain George Vancouver sailed into English Bay, brought peace to the Native communities of the region and who were subsequently honoured by being transformed into the twin peaks that dominate the North Shore skyline. Today, these peaks are widely known as the Lions.

No matter how far up the mountainside neighbourhoods have crept, the wilderness still influences the North Shore. Black bears and cougars prowl backyards on the perimeter of habitation. Hapless hikers, skiers, and snowboarders routinely lose their way and wait (and pray) to be saved by the North Shore Rescue Team, a volunteer group who selflessly put their own lives at risk to track down missing adventurers.

Despite the outward appearance of urbanity, the North Shore contains some of the most rugged terrain in the province. The mountainous topography represents the forward perimeter of land pushed out to the coast by the mile-thick glacial ice pan that held sway 12,000 years ago. The Coast Mountains, which begin on the North Shore and sweep north along the British Columbia coast and through Alaska, are the tallest range in North America and among the most heavily glaciated.

Due to the North Shore’s steep incline, much of the outdoors activity that takes place here will get your heart rate up within minutes of starting out, whether you adventure on foot, by bike, or on skis or snowboard. Pothole lakes are the refreshing reward for those who explore the higher reaches in summer. Just as prized are the rugged beaches on Burrard Inlet that await those who prowl the shoreline. Rain or shine, you can always count on finding shelter beneath the broad branches of the ancient and second-growth forests.

Whistler/Sea to Sky

Intensely scenic, the Sea to Sky Highway (Highway 99) crosses paths with two historic routes, the Pemberton Trail and the Gold Rush Heritage Trail, which linked the coast with the interior in the days before the automobile. Along these ancient pathways, generations of Coast Salish people traded with their relations in the Fraser Canyon, while in the 1850s, prospectors stampeded north towards the Cariboo gold fields. In 1915, the Pacific Great Eastern railway began service between Squamish and the Cariboo. For those in search of outdoor recreation, the railway proved an ideal way to reach trailheads in Garibaldi Provincial Park and fishing camps such as Alta Lake’s Rainbow Lodge, situated at the foot of London Mountain.

By the mid-1960s, the prospect of skiers heading from Vancouver to the fledgling trails on London Mountain – by this time renamed Whistler Mountain – prompted the provincial government to open a road north from Horseshoe Bay through Squamish to Whistler. Space being at a premium along steep-sided Howe Sound (North America’s southernmost fjord), the road and railway parallel each other for much of the 45 km between Horseshoe Bay and Squamish at the head of the sound. By 1975, the highway was pushed through to Pemberton, and by 1995 the last stretch of gravel road was paved between Pemberton and Lillooet. (Highway 99 and the railway part company in Pemberton but link up again at Lillooet.) Today, vehicles breeze along the entire route in five hours, the time it took in the 1960s to make the journey just from Horseshoe Bay to Whistler.

Both the railway, which now departs from its southern depot in North Vancouver, and Highway 99 have helped introduce visitors to the backcountry region in the Sea to Sky corridor. (The 12-hour train trip between North Vancouver and Prince George in the Central Interior is one of Canada’s most scenic rail journeys. Travellers can choose to disembark or be picked up just about anywhere along its route.) Certainly, Whistler’s success as a resort destination has propelled development, both commercial and recreational, in other parts of the region, particularly Squamish and Pemberton. So too has the popularity of the mountain bike and the sport-utility vehicle. The pace of mountain-bike trailblazing carries on today with the same zeal once devoted to the creation of new ski runs, while logging roads no longer intimidate drivers in search of backcountry getaways as they once did. And it’s not just the proximity to Greater Vancouver that drives this expansion. The landscape itself just happens to be some of the most ideal terrain for outdoor activity in British Columbia.

Squamish (population 16,000) is a relief. Smaller than Vancouver, larger than Whistler, and equidistant from them both, Squamish is the envy of the south coast. It has so many things going for it – location, geography, wildlife, weather – that as forestry declines as the town’s major employer, tourism and outdoor recreation have taken on greater importance. Travellers have always been drawn to Squamish, from the days of the Coast Squamish people, who journeyed between Burrard Inlet and STA-a-mus at the mouth of the Squamish River, to more recent times when steamships began ferrying anglers, climbers, and picnickers here over a century ago. There’s a rich history to the Squamish region, and the best way to experience it is through a favourite outdoor activity. No matter what your pleasure, you’ll follow paths laid down by fellow admirers who’ve cleared the way.

Something magical happens when you arrive at the summit of the small valley that contains Whistler. A cluster of little lakes is gathered here, reflecting the outline of the mountains high above. Alta Lake is the great divide in the Sea to Sky corridor. Water flowing from its south end reaches the Pacific via the Cheakamus and Squamish Rivers, while water flowing from its north end in the River of Golden Dreams eventually reaches the ocean through the Harrison watershed and the Fraser River. No other valley in the Sea to Sky region has such a wealth of small and medium-sized lakes. No other lakes have scenery quite like this to mirror. When you let your eyes rise from the reflection to admire the real thing, the contours of the ski runs on Blackcomb and Whistler Mountains pattern the forested slopes. Above the tree line, you can still see remnants of the most recent ice age in the glaciers that encrust the highest peaks. Take a deep breath of the freshest air imaginable.

Pemberton/Lillooet

For over a century, Pemberton existed in something less than splendid isolation from the rest of the Lower Mainland. Travel in and out of the valley was regulated by the railway. When a highway was finally punched through from Whistler in 1975, the long period of separation ended. At first, there was only a trickle of traffic along this stretch of Highway 99, mostly logging trucks southbound for Squamish and the occasional carload of climbers headed north to Joffre Glacier. In the past decade, the pace of tourism has accelerated. The 1986 World Exposition in Vancouver kick-started bus tours to Whistler and beyond; in subsequent years, the paving of the Duffey Lake Road made the corridor between Pemberton and Lillooet a breeze to explore. (Until then, the standing joke was that this former logging road was always under two feet of mud and four feet of snow.)

Today, Pemberton is experiencing a growth in both visitors and new arrivals who are taking up residence in this agriculturally and recreationally rich valley. Quick access to hiking, climbing, mountain biking, and backcountry ski-touring routes is one of the main reasons for the surge in popularity. Unlike Whistler, very little of this activity is centred in the small town, the population of which is estimated at between 500 and 4,000, depending on who you consult. Instead, a variety of wilderness outfitters, guides, and ranches are located throughout the 30-mile (50-km) stretch between the head of Lillooet Lake and the north end of the valley. This is the traditional territory of the Lil’wat Nation, who today are headquartered in Mount Currie and D’Arcy, with smaller communities sprinkled along Lillooet Lake. From the time of their first contact with Europeans, the Lil’wat have always been characterized by their friendliness towards visitors. Although such openness hasn’t always worked to their advantage (they are now involved in complex treaty negotiations with the provincial government), you’ll be welcomed at events such as the Lillooet Lake Rodeo, held each May in Mount Currie, and at the salmon festival in D’Arcy in August.

As the Sea to Sky Highway winds between the Cayoosh Pass, Lillooet, and Hat Creek, it passes through the most notably varied terrain of its entire length. Transitions between the other biogeoclimatic zones are more subtle. Here the change from coastal temperate zone to aridity occurs abruptly. Much of this area lies in the rain shadow of the Coast and Cascade Mountains. By the time the last moisture in the clouds has been raked off by the peaks around Cayoosh Pass, there’s little left to water the countryside to the east. Ponderosa pine and sage take over from western hemlock and devil’s club.

The Sunshine Coast

The world’s longest highway, the Pan-American (also named Highway 101 in parts of the United States and Canada), stretches 9,312 miles (15020 km) from Castro on Chile’s south coast to Lund on BC’s Sunshine Coast. The 87-mile (139-km) stretch of Highway 101 between Langdale and Lund outperforms its size. Dozens of parks with biking, hiking, and ski trails; canoe and kayak routes; beaches; and coastal viewpoints are easily reached from the highway. Campsites are plentiful, and except in July and August and on long weekends from May to September, you won’t have any difficulty in finding a place to pitch your tent or park your RV.

The Sunshine Coast lives up to its name. With an annual total of between 1,400 and 2,400 hours of sunshine – that’s an average of 4 to 6 hours per day, depending on where the measurements are taken – bright days outnumber gloomy ones by a wide margin. The Sunshine Coast benefits from a rain shadow cast by the Vancouver Island mountains, which catch most of the moisture coming in off the Pacific Ocean. In winter, clouds regroup in the Coast Mountains to the east of the Sunshine Coast and provide sufficient precipitation in the form of snow to coat trails for cross-country skiing. The remainder of the year it falls as rain, British Columbia’s ‘liquid sunshine,’ which nourishes the temperate rain forest.

The Sunshine Coast is split into two portions on either side of Jervis Inlet. Roughly speaking, the southern half between the ferry slips at Langdale and Earls Cove occupies the Sechelt Peninsula, while the northern half between the ferry slip at Saltery Bay and Lund sits on the Malaspina Peninsula. The coastline is deeply indented by the Pacific Ocean at Howe Sound, Jervis Inlet, and Desolation Sound. Jervis and Desolation are of such fjordic proportions that they attract a steady stream of marine traffic throughout the summer months, when brilliant sun shines on the countless cataracts that cascade down the sheer-sided slopes. Come moodier months, the clouds become ensnared in the snaggle-toothed peaks, making you feel just as pleased to stick to the sunnier coastline.